‘Winners and losers’ in the battle for Detroit development funds

‘Winners and losers’ in the battle for Detroit development funds - BridgeDetroit

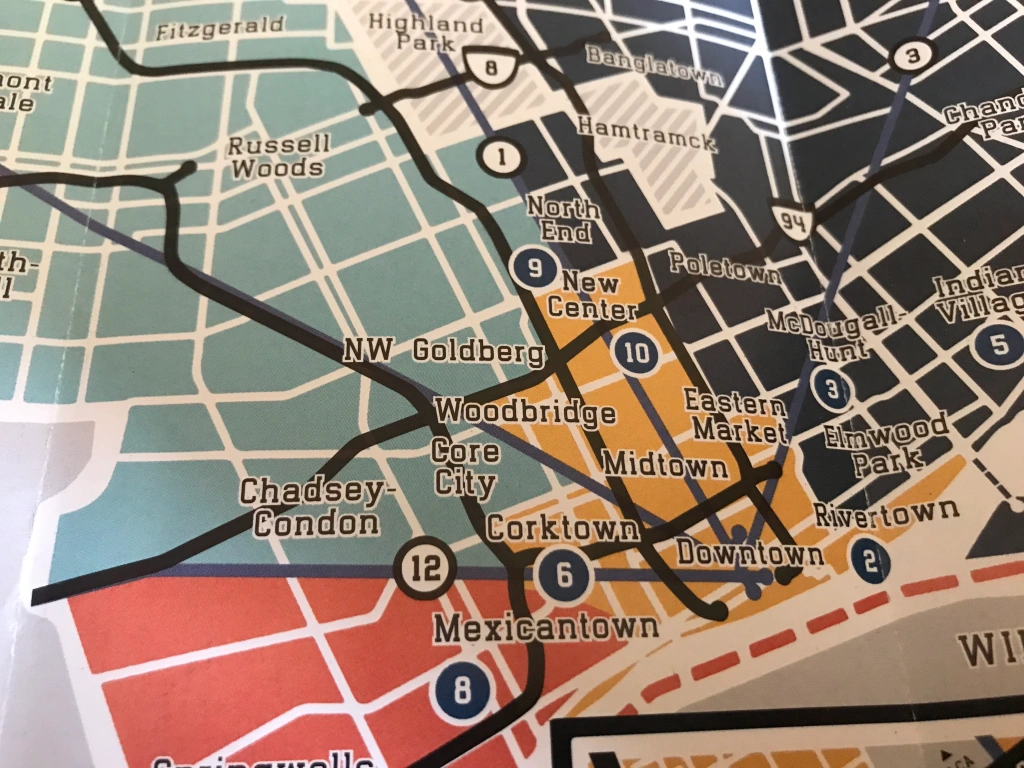

Millions of dollars in pandemic relief funds are flowing to downtown Detroit for projects aimed at promoting economic growth and improving public spaces, but some Black developers who lost out on the funding say the city missed a vital opportunity to invest in neighborhoods.The funding competition reignites tension between smaller developers who want more support for communities outside of the city’s core and the mega projects envisioned to shape Detroit’s downtown into a destination for the region and its longtime residents.The Michigan Strategic Fund approved 22 grants in September through the Revilitization and Placemaking (RAP) grant program, sending $83.8 million in pandemic relief to cities and developers. Fifty-nine Detroit developers submitted applications seeking a combined $150 million, but the Downtown Detroit Partnership was the lone Detroit recipient. The city’s nonprofit economic growth agency received $13.7 million for a bundle of eight downtown projects to enhance parks, retail and housing. ple Text

The decision frustrated Black developers like Brandon Hodges, founder of TRIBE Development, who submitted two unsuccessful applications for neighborhood projects. Hodges said smaller developers who struggle to finance projects saw the RAP program as a “once in a lifetime opportunity.” The exclusive support for downtown, he said, left a bad taste in their mouths.“We don’t really have a ton of other funding sources, programs or entities that advocate for the neighborhoods in the same way that, say, the Downtown Detroit Partnership does for downtown,” Hodges said. “That was one of the things I was most frustrated with, and I think a lot of people were, too. The downtown has a lot of advocacy. It has a lot of corporate partnerships. It has a lot of tax base it can capture. The neighborhoods don’t, and so we just missed an opportunity.”

The federal funds were meant to support the rehabilitation of vacant, underutilized, blighted and historic structures and to develop public social-zones and outdoor dining. The RAP program is designed to address the impacts of COVID-19, and projects must prove they will help grow population and tax revenue. DDP joined forces with influential downtown players like billionaire Dan Gilbert’s real estate company Bedrock Detroit, Lansing-based Karp and Associates, The Greektown Neighborhood Partnership and Paradise Valley Conservancy. The combined grant application states these groups “represent the major stakeholders” downtown, and their partnership is “unprecedented in our organizations’ history.”

The group aims to create new reasons to visit and live downtown, offset the pandemic-era loss of office workers, stimulate new business and grow tax revenue for the city. Eric Larson, DDP’s chief executive officer, said the downtown projects are an important piece of Detroit’s strategy to attract new visitors and residents, but he understands why neighborhood developers may feel like they were shorted. “We are very sensitive to the fact that we represent a very small piece of what is the overall city, not only in terms of geography, but also in terms of population and need,” Larson told BridgeDetroit. “It is honestly a struggle that we deal with internally on a regular basis; to try and be really genuinely understanding and sensitive to the broader needs.“In these processes, there’s winners and losers,” he added. “That part is tough for us and it’s tough for those that didn’t get picked.”

Downtown’s ‘inflection point’

Three prominent downtown parks – Capitol Park, Cadillac Square and Grand Circus Park – are slated for “place-making enhancements” overseen by DDP. The downtown partnership will receive $3 million for its parks investments, with the remaining $11.75 million spread between the private developers. Real estate projects can receive up to $5 million each. The Greektown Neighborhood Partnership received funds to transform Randolph Plaza into an outdoor hangout at the gateway to Greektown. Investments in Paradise Valley Cultural and Entertainment District will seek to improve the park area, remake the entryway into the district and support Black-led residential and cultural developments. Karp and Associates is planning to rehabilitate the vacant 7-story former United Savings Bank of Detroit building on Griswold into a mixed-used development. The $13 million project will add four stories to the 101-year-old building, as well as ground-floor retail space, commercial opportunities and 25 apartments, of which five will be offered at a discounted rent. RAP funding will also support Bedrock’s redevelopment of the Harvard Square Center building on Broadway, which sits across from the Z-Lot parking garage owned by Bedrock. Detroiters have long struggled with changes downtown, raising questions about who is served by the flashy new developments in the city’s core. New housing units are largely viewed as too expensive for the majority of residents living in a city where the median income is just under $32,500. Accessibility is another issue for residents who say getting downtown from their neighborhoods can prove challenging due to poor public transportation options. “We see downtown as the suburbanites’ party environment,” said Paul Jones, a lifelong Detroiter and vice president of the transit advocacy group Transportation Riders United. “It’s like this empty place that can take on different roles to support big events for the region, but the rest of the things to make that place work are not there. Things as simple as grocery stores. If you’re trying to find a bottle of water in downtown Detroit after 10 p.m., where do you even do that? "Wayne Curtis, a Jefferson-Chalmers resident, said Black Detroiters are on guard when they venture downtown. Curtis said he feels like a target for police and an unwanted presence for non-Detroiters visiting the newer high-end retailers and upscale restaurants. "You drive through the city (neighborhoods) and see nothing but mounds of vacant land in the same spots. Now, all of a sudden, downtown is going to get rebuilt and money is coming in from everywhere,” Curtis said. “Downtown wasn’t built for Detroit’s working class, they’re getting rid of the working class. I’m very resentful of that. They’re bringing in this new political gentrified culture. "Daisy Jackson, a fourth-generation Detroiter and vice president of the Field Street Block Club in the Islandview neighborhood, said she doesn’t feel comfortable downtown either. She ventured down for a pedal bar tour for her 67th birthday, but said she was deterred from coming back after spending $60 to park in a surface lot near Comerica Park.“To me, it’s all about gentrification,” Jackson said. “Run the African Americans out and bring the Caucasians in. It’s not for longtime Detroiters. "Larson acknowledged the DDP has “wrestled with” how to make downtown an inclusive place. “We don’t always get it right,” Larson said. “Dan Gilbert, and the level of attention on his entrance on the downtown stage, obviously had some real pros to it, but one of the things it did cause was pushback on is, ‘Is the city really open and inviting for everyone, or is this becoming just sort of this corporate company town?’” Larson said. “(Gilbert) never intended that, their team never intended that, but perception is always 99% of reality. "The DDP’s grant application states downtown is at an “inflection point.” The pandemic caused a steep 60% drop in daily downtown office workers, according to DDP. Larson said the office population is unlikely to fully recover; the downtown’s future will be paved by focusing on those who live and “play” there. "We won’t have the same level of demand for the current occupancy as leases roll,” Larson said. “A great example is Deloitte, (which) moved out of the Renaissance Center when its lease rolled and into WeWork space (downtown). We’ll see more of those kinds of things … I also think we’ll see new offices come to the market. I don’t mean that we’re done attracting new businesses and new employees, but it will take some time.” The exodus of white-collar office workers carries major implications for Detroit’s budget. The city lost $54.5 million in income tax revenue last fiscal year due to the decline of in-person work, and September projections from the Office of Budget show more than $30 million could be lost annually over the next five years. “Detroit has a ton of opportunity, not only to eat, dine, drink and shop, but also to experience,” Larson said. “Pre-pandemic we had 33 million non-office, non-residential visitors in the downtown. During the pandemic, it dropped to 22 million, but we’re on track to be well in excess of 33 million (visitors) in 2022. That’s a pretty good example of a level of activity that we need to concentrate on, to harness and continue to think about. “How do we expose people throughout the region, not just the City of Detroit,” Larson said, “to all of what Detroit has to offer? "Census data shows Detroit has more than 7,200 downtown residents, an increase of about 45% since 2011. The vast majority of downtown housing is filled with renters. Of the approximately 4,500 downtown residential units, the DDP estimates only around 300 are owner-occupied. Millennials are the dominant generation living downtown – 61% of residents are between the age of 19 and 34. Census data shows around 40% of downtown residents are Black, despite making up 77% of the city’s population. Larson said the planned improvements are not trying to cater to any particular group. Amenities like food truck programs, night markets, outdoor exercise classes and free community events are meant to create welcoming spaces for everyone, he said. Jones, of the transportation riders group, said there should be more amenities for families and seniors, things like picnic areas, public restrooms and open parks that don’t require Detroiters to open their wallets. An experience with private security officers who booted Jones from Grand Circus Park when he was trying to read in his hammock lingers, he said, as an example of how spaces aren’t inclusive.

“One of the DDP security guards kept saying ‘our client doesn’t want people using this space that way,’” Jones said. “I’m like ‘what do you mean your client? This is a park.’ "Chase Cantrell, executive director of Building Community Value, a nonprofit community development group that provides resources to local developers, said downtown Detroit is divided. “There are spaces downtown where Black people go, but downtown itself is segregated,” Cantrell said. “The extent that there is comfort among Black people going into certain spaces, you can see a tendency of Black people staying together and white people staying together. "Cantrell, a partner on one of Hodges’ development projects that failed to secure RAP funding, said he sees more downtown arts and entertainment being curated for Black Detroiters, but he doesn’t see enough Black-owned downtown spaces. “The real opportunity for ownership is in the neighborhood,” he said. “People point to the Avenue of Fashion. The reason it’s so vibrant is you have those neighborhoods around it.”Hodges said Bedrock’s Monroe Street Midway, an outdoor skating and sports facility next to Campus Martius, is a welcome addition to downtown. It taps into Detroit’s roller skating subculture, he said, and provides a creative class of artists and designers with murals and storefront displays.“Those things resonate with people because they see themselves in those spaces,” he said.

Hodges pointed to other Black-owned staples like Hot Sam’s, the oldest men’s clothing store downtown, and Cafe d’Mongo’s Speakeasy, but said by and large it seems harder for Black entrepreneurs to gain a foothold. Still, Hodges notes access to downtown storefronts is improving for Black retailers in the last five years. Bedrock’s investment in the Campus Martius area, he said, has created new opportunities for small businesses, and he’s seen Bedrock put more emphasis on giving Black-owned popups and businesses opportunities. “This is still a majority-Black city,” he said. “To create a downtown that feels vibrant for everybody, you have to carve out those spaces and opportunities for everybody.” le Text

‘It just begged a lot of questions’

The Detroit Economic Growth Corp. provided 45 letters of support to Detroit applicants for the RAP funding. Capital Impact Partners, a nonprofit community development financial institution, submitted another proposal that combined several BIPOC-led development projects in neighborhoods outside of downtown. None were successful. The Michigan Economic Development Corp. received 185 applications requesting $500 million. Only 22 applications secured support from the $100 million fund. A remaining $16.2 million in grants will be announced at a later date, according to the MEDC.The DDP’s joint application included the most partners and projects of any that were awarded. It also secured the largest grant in the state, followed by Flint ($10 million), Grand Rapids ($9.4 million) and Muskegon ($6 million). Lori Mullins, director of Community Development Incentives for the MEDC, said the DDP’s joint application stood out because it focused on the pandemic-era loss of office workers. The RAP funding was specifically geared toward addressing the negative economic impact of COVID-19. Mullins said the RAP funding is just one tool available for neighborhood developers. MEDC, she noted, has approved $60 million for 38 projects outside the downtown area since January 2020. MEDC plans to follow up with applicants who didn’t receive funding through RAP to explore other resources that are available. "Nearly 83% of the awards that we’ve made in Detroit (since January 2020) have gone to areas outside the Downtown Development Authority boundaries,” said Michele Wildman, vice president of Economic Development Incentives for MEDC. “In this particular case, it was a complex federal program and this particular proposal resonated as a result of its focus on downtown and its efforts to proactively address things we’ve seen in the last couple of years relative to the shift in the work environment. Hodges said his neighborhood developments will still move forward but have to be scaled back, with fewer affordable units, pop-ups for small businesses and public space enhancements than originally planned. Hodges is planning renovations of two buildings expected to cost $8.3 million total. The redevelopment of a vacant two-story building on the corner of East Warren and Yorkshire would create six new apartment units and 4,000 square-feet of ground floor retail space. All of the units would be affordable for Detroiters earning between 60% and 70% of the area median income, Hodges said, which is between $42,960 and $50,120 for a two-person household. Hodges also plans to renovate a nearby parking lot and plaza and find a restaurant tenant that reflects the preferences of the neighborhood. Another redevelopment Hodges is planning in the Bagley neighborhood would create 10,000 square feet of ground floor retail space for an artisan market that can hold 20 to 30 vendors, similar to Rust Belt market in Ferndale, but it would focus solely on Black and brown Detroit-based entrepreneurs. Hodges plans to add a second level to the building for event space and offices for emerging businesses and for the shared use of vendors on the first floor.“What you kind of see in the application is the largest portion of the grant funding is going to Bedrock and Richard Karp; it’s going to real estate developers that are already getting a lot of support in other ways,” Hodges said. “It just begged a lot of questions. There’s a lot of conversations that are going to be had about this, just simply from an accountability perspective.”Karp, who noted he was born and raised in Detroit, said that his project wouldn’t have been possible without the RAP funding. The Griswold building was stripped of its historic facade, meaning it’s not eligible for state or federal historic tax credits, he said. “In order to increase the tax base that Detroit’s neighborhoods need – for street lighting, police and fire, garbage pick up, etc. – we have to make sure our downtown is economically healthy so it can pay taxes, both income and property,” Karp said in an email to BridgeDetroit. “COVID has taught us we can no longer rely on expanding office leasing to do so, so that leaves us with housing and entertainment. The new residential tenants we bring into (Detroit) pay city income tax and patronize shopping, dining, and entertainment.”Cantrell argues that creating a vibrant downtown “is not the thing that’s going to retain the Black middle-class,” which Detroit has hemorrhaged for decades. “You may get folks from Birmingham coming in for the weekend but you will not get (Detroit) folks who are in the middle-class,” he said. “You need to have amenities in the neighborhoods. What’s going to keep someone in Bagley, or Sherwood Forest or the University District? It’s not that we have a vibrant downtown. It’s that we have something you can walk or bike to.”RAP’s investment downtown also struck a blow for developers working outside the 10 areas supported by the city’s Strategic Neighborhood Fund, Cantrell said. “Detroiters have the right to ask, ‘if every neighborhood has a future, how long do we have to wait on that in the future?,’” Cantrell said in reference to Mayor Mike Duggan’s former campaign slogan. “There are some neighborhoods that will not be invested in, in the next decade. How do we frame fairness for residents who live there?”